— Billy The Kid, as quoted in the Daily New Mexican, March 28, 1881

The Lincoln County War was exceptionally violent, and much of that violence occurred in the small town of Lincoln, New Mexico. But murder and mayhem were facts of life there long before Billy the Kid and the Regulators collided with followers of L.G. Murphy. In fact, the entire history of Lincoln in the late 19th century was punctuated with tragic accidents, senseless violence, questionable examples of frontier justice and acts of revenge. During the decade of the 1870s alone, more than 50 people were killed along the one-mile stretch of dusty road that curved through Lincoln—a fact that led President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1878 to declare it “The Most Dangerous Street in America.”

The following are just a few examples of the deadly violence that plagued Lincoln in those years. Some of those who died were innocent victims, some were notorious criminals, but most were just typical denizens of the Western frontier. They were tough, independent people whose lives reflected the brutal reality of the conditions under which they lived.

Tragic Accidents

— All Images and artwork Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted —

On September 2, 1876, Josiah “Doc” Scurlock accidently killed his friend Mike Harkins in the carpenter shop behind the Murphy-Dolan Store. Scurlock was showing off his new “self-cocking pistol” when it accidently discharged. The bullet struck Harkins just below the left nipple and pierced his heart, killing him instantly.

Two years later—on February 18, 1878—Lincoln was rocked by news of the murder of John H. Tunstall. Capt. George Purington sent a few soldiers from Fort Stanton to Lincoln the next day in hopes of keeping the peace. Then, on February 21, he sent a dispatch rider to Lincoln with a message for the detachment. The rider, unaware that a sentry was posted at the west end of town, attempted to gallop past the courthouse. The sentry, Pvt. Gates, failed to recognize his fellow trooper, though both were members of the same company of the famous 9th U. S. Cavalry. Gates fired just once, but Pvt. Edward Brooks, a 29-year-old native of Kentucky, was dead as he fell from the saddle.

Senseless Violence

On the evening of October 21, 1874, Lyon Phillipowski was having a few drinks in the Billiard Room at the L.G. Murphy & Company store. Phillipowski was married to Teresa Padilla, and they had an eight-year-old daughter named Lolita. He was also a deputy sheriff of Lincoln County. When it came time for bartender William Burns to close up, Phillipowski was angry. He wasn’t ready to go home. Burns insisted. Phillipowski ominously warned Burns that he would “see” him outside. Sure enough, as Burns left, Phillipowski approached and reached for his gun—Burns was ready, and Phillipowski collapsed, mortally wounded, onto the muddy street. He died the next morning.

On October 10, 1875—former sheriff Alexander H. “Ham” Mills confronted Gregorio Valenzuela along the street in Lincoln. Valenzuela and Mills had been neighbors in San Patricio in 1870, so had known each other for several years. Mills owed Valenzuela money, but was either unable or unwilling to pay. They argued, and Valenzuela called Mills a “damned Gringo.” Mills pulled out a gun and shot Valenzuela, a husband and father, dead. He was convicted of fifth-degree murder, but L.G. Murphy obtained a pardon for Mills from Gov. Samuel B. Axtell.

Frontier Justice?

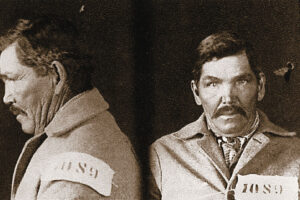

— Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin

William Wilson once bragged that he had done time in Sing Sing Prison. He drifted west to Lincoln, and on August 1, 1875, he murdered Robert Casey near the Wortley Hotel. Wilson claimed that Casey owed him $8 in back wages. He was arrested, tried for murder and sentenced to death by hanging. This was the first legal hanging in Lincoln County, and Sheriff Saturnino Baca was anxious to get it right. On the appointed morning—December 10, 1875—Wilson was brought to the gallows under guard. The sentence was read out loud as the hangman prepared Wilson for the “long drop,” then the trap was sprung.

Unfortunately, the fall failed to snap Wilson’s neck. His body danced at the end of the rope for several minutes, but eventually he stopped struggling. Thinking him dead, Sheriff Baca cut the rope. The crowd was invited to view the remains, and a local woman realized that Wilson was still breathing. Not one to leave a job half finished, Sheriff Baca had William Wilson hoisted back up on the gallows and hanged for a second—and mercifully final—time.

George Washington, a former employee of A. A. McSween, was “trying to shoot a stray dog” in June 1879 at his home near the ruins of the McSween House. Somehow, a bullet intended for the stray hit Washington’s own wife, Luisa Sanchez, and their infant child, killing them both. The circumstances were highly questionable, but there were no witnesses. Later, when Washington attempted to elope with a teenage girl, unspoken suspicions were aroused. Washington was caught, returned to Lincoln, and late one night he was taken from the jail and lynched.

Revenge

Sometime in early December 1871, 48-year-old Avery M. Clenny stopped by Pete Bishop’s saloon in Lincoln. Clenny owned a store in Hondo and was in town on business. He talked with Bishop briefly, but Bishop had to go to his storeroom to fetch something. Two younger men, George Van Sickle and Calvin Dodson, then entered the saloon. It’s unclear why, but when Bishop returned he found Van Sickle and Dodson administering a severe beating to Clenny. Bishop retrieved a pistol that he kept behind the bar and chased Dodson and Van Sickle into the street near the Montano Store, shooting at both men. Van Sickle survived; Cal Dodson did not.

The Horrell brothers were a notorious group of Texas outlaws. One brother, Ben, was carousing in Lincoln with friends when he was killed in a confrontation with Constable Juan Martinez on December 1, 1873. The surviving Horrell brothers brooded over their loss for about three weeks, and then on the evening of December 20, they rode into Lincoln bent on revenge. Hearing music coming from Chapman’s Saloon, they surrounded the building and fired through the doors and windows. The music was for a wedding dance, and the building was crowded with men, women and children. Four Lincoln men died that night: father of the bride Isidro Patron, Isidro Padilla, Mario Balazan and Jose Candelaria. Two women and a boy were wounded. Not satisfied, the Horrells killed at least eight more people on their way back to Texas.

Lincoln is most famous for its association with Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, L.G. Murphy and other notable contestants in the Lincoln County War. But the town’s legacy of violence extends well beyond that feud. Virtually every step one takes during a stroll down the sidewalks of Lincoln’s main thoroughfare is connected with another fatal incident. It has unquestionably earned its presidential distinction: The Most Dangerous Street in America.

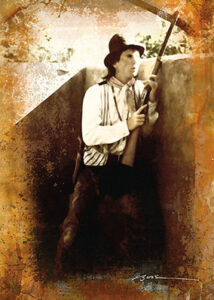

The Kid peeks out from the smoke-filled kitchen as he and the McSween men get ready to make a break. The heat must have made it almost unbearable.

— New Mexico State Records Center & Archives —

Anatomy of the Killing Fields

It is a half mile from one end of Lincoln to the other and, on just this street, 49 men and one woman were killed in the approximately 10-year period of the Lincoln County War and its aftermath. At about the halfway point, and in the heart of the killing fields, lie several locations, at left, where most of the shooting deaths occurred.

On the night of July 19, 1878, in what is known as the “Big Killing” and the “McSween Fight,” at least five men were killed when the Murphy-Dolan forces surrounded the McSween faction and burned them out.

French and the Kid (who some think was trying to retrieve his Winchester which Brady had taken from him previously) hotfooted it back to the wall.

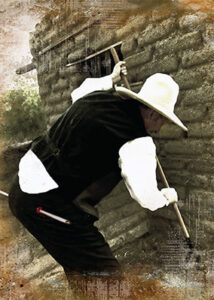

Deputy George Hindman is hit and falls. Brady, who is hit by a dozen balls, says, “Oh, Lord” and tries to get up, but another round of shots hit him, and he falls back, mortally wounded.

Billy the Kid and six of the Regulators are in the corral behind the Tunsdall Store when they spot Sheriff Brady riding into town. Firing from behind a ten-foot wall, they ambush Brady and four deputies when they pass on foot, walking east past the store.

the Regulators firing from Tunstall’s corral tore through his buttocks.

Attempting to escape out the back door of the burning house, five men were killed: Alexander McSween, Francisco Zamora, Vincente Romero, Harvey Morris and Robert Beckwith. Another, Yginio Salazar, survived with severe wounds and crawled off. He lives. Virtually next door from the McSween house is the Tunstall Store, where an earlier ambush by the Regulators results in the death of Sheriff Brady and his deputy George Hindman. Across the street, hoeing onions in his back yard, Squire Wilson is hit by a stray bullet and falls forward as it passes through his buttocks.

Tim Roberts is the deputy director for New Mexico Historic Sites, responsible for all aspects of preservation and interpretation across the state’s eight historic sites and properties. He is the former manager at Lincoln and Fort Stanton Historic sites.

Scott Smith is currently the instructional coordinator at Lincoln and Fort Stanton Historic Sites. He has nearly 30 years’ experience with New Mexico Historic Sites, including time as manager at Fort Sumner and Coronado Historic sites.

![]()