Take a look behind the scenes of the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s crime laboratory. Including cases about the kidnap of a 12-year-old girl from her own home, the murder of 23-year-old Robin Bishop in 1982, the killer who randomly shot and killed 5 men in Ohio, and how a case was built against a paedophile who brutally raped and murdered Nancy Newman and her two children.

In 1992, Richard Fry of Canton, Ohio read about the seemingly random murders of five men, most of them outdoorsmen, in eastern Ohio during the four year period from 1989 to 1992.

A sniper had murdered the following:

Donald Welling, 35, while walking or jogging on Tuscarawas County Road 94, on April 1, 1989.

Jamie Paxton, 21, while deer hunting in Belmont County, on November 10, 1990.

Kevin Loring, 30, while deer hunting in Muskingum County, on November 28, 1990.

Claude Hawkins, 48, while fishing at Wills Creek in Coshoction County, on March 14, 1992.

Gary Bradley, 44, while fishing near Caldwell in Noble County, on April 5, 1992.

However, Fry knew that on weekends Dillon enjoyed driving around the areas in which the aforementioned men had been killed. Fry also knew that Dillon possessed weapons capable of shooting accurately from a long range. Finally, Fry remembered a disturbing conversation with his friend when the two of them had attended a gun show. Dillon had an odd look on his face as he twice repeated this question to Fry: “Do you think I’ve ever killed anyone?”

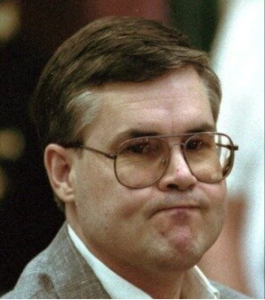

Fry contacted the office of Tuscarawas County Sheriff Walt Wilson and was soon talking about his friend Dillon with the Sheriff and other investigators. According to Michael Miller, who prosecuted the case against Dillon, Fry had the eerie sense that “Dillon was the type of person who could do something like this.”

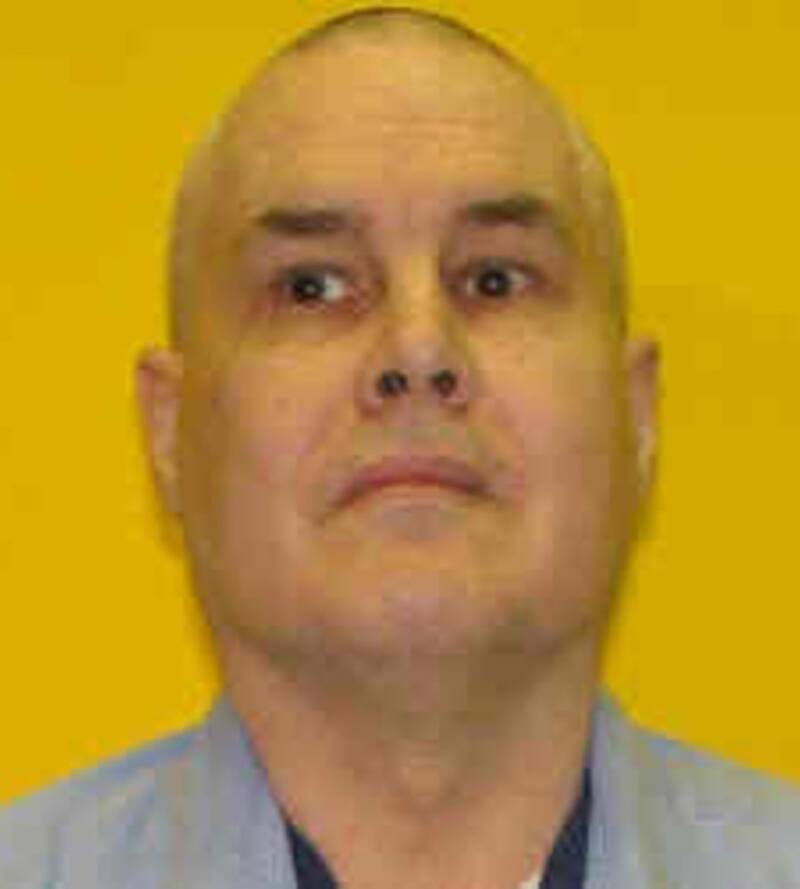

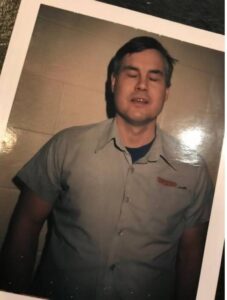

With no hard evidence, members of a task force formed to look into these sniper slayings began following Dillon. They arrested him on a weapons charge and his photograph appeared in the newspaper. A gun dealer saw the picture and recalled a gun called a Mauser that Dillon had sold to him. According to an article by David Kohn, Miller related that the gun dealer “still had the Mauser and he called the task force. That Mauser was ultimately taken to the FBI lab and it was confirmed that it was used in one of the homicides.” That homicide was the murder of Gary Bradley.

A search of Dillon’s residence showed that he had kept newspaper clippings about some of the murders.

Dillon soon admitted to all five murders. His defense attorneys asked psychologist Jeffrey Smalldon to examine Dillon to determine if an insanity defense might be viable. Smalldon recalled that Dillon was “very smart, an IQ of around 135, in the superior range of intelligence.” Dillon related how he often spent weekends driving around rural Ohio looking for someone isolated, whether jogger, fisherman, or hunter, to shoot to death with a rifle.

However, that voice was not the alien voice that a schizophrenic might “hear” but the voice of Dillon’s own thoughts since when Smalldon asked if the voice was that of someone else, Dillon freely admitted, “I know it was me. It was my own voice. It was a voice in my head.” In addition to the five murders, Dillon had set more than 100 fires in country areas and killed more than a thousand pets and farm animals. Smalldon told the defense attorneys that Dillon was not insane and a mental defense would not work. After receiving the agreement of the victims’ families, Miller offered a deal by which Dillon would confess and accept life imprisonment so prosecutors would not pursue a death sentence against him. Dillon accepted the deal and make videotaped confessions of his crimes.

In a blasé manner, he described the shooting of Kevin Loring.

Investigator: “How far away was he from you when you shot him?”

Dillon: “Seventy-five feet maybe.”

Investigator: “Where did you shoot him at?”

Dillon: “Right between the eyes.” Investigator: “Is that where you aimed for?”

Dillon: “Yes.” Investigator: “Did you walk up to him and look at him?”

Dillon: “No, didn’t come close.”

Investigator: “But you’re sure he was dead?”

Dillon: “Yeah, yeah. His hat blew straight up about 20 feet.”

When Dillon was asked why he murdered Loring, Dillon replied, “I don’t know, just something came to me.”

Although all victims were strangers to Dillon, he became oddly interested in them after their deaths. He visited the graves of the men he murdered. He even went to the trouble of visiting Loring’s hometown of Duxbury, Massachusetts to find out more about him. Dillon told police, “I went to New England last year with my wife and I looked up on the microfilm on the Plymouth Library where that guy lived and everything. He was from [the] Duxbury area. I just read you know, see what, who the hell he was. I didn’t know who he was.”

Dillon wrote an anonymous letter to the newspaper about the murder of Jamie Paxton in which Dillon stated, “I am the murderer of Jamie Paxton . . . I felt the Paxton family should know the details of what happened. I thought no more of shooting Paxton than shooting a bottle at the dump.” However, Dillon claimed in police interviews that he had regrets about the Paxton murder because Paxton was only 21 when Dillon slew him. Dillon said, “I felt bad about the kid, you know. I didn’t know he was that young. I couldn’t see how old he was from a distance. I thought he was 30, 35. I didn’t know he was that young. . . . [I] blew that kid away you know, he had his whole life ahead of him and I blew him away. You know, I felt sorry for him.”

Smalldon believes Dillon may not be telling the entire truth about his feelings and motivations. The psychologist speculates, “I think he’s holding back because he wants to remain a puzzle. He would ask me, ‘Have you ever met anyone as complicated as me? Can you understand this? Am I, is this behavior, as perplexing to you as it is to me? There’s never been a crime like this in Ohio, has there? No motive. No contact with the victims. How could you figure that out?’ And then he would shrug and say, ‘I don’t know.”

Miller agrees that Dillon got a special kick out of presenting himself as an enigma. “I think that he felt he was something special,” Miller comments. “And when he was arrested and the plea and so forth, he’s not a guy that used a jacket to cover his head, you know, he looked into the camera with a smirk.” An investigator asked Dillon if he would have continued murdering had he not been caught. “Probably,” Dillon answered. Miller once noted that one of the victims had long hair. He asked Dillon if he considered the possibility that that individual was a woman. Dillon replied, “What do you think? I couldn’t care less. It wouldn’t have made any difference to me.”

While imprisoned, Dillon often wrote Smalldon. In some letters, Dillon said he wished he had sought mental health help before the crimes. He expressed regret for what his crimes had done to his own family.

Dillon died of natural causes in prison on October 21, 2011. He had been taken to the prison wing of the Ohio State University Medical Center three weeks previously for an illness not made public. Randy Ludlow reports, “Until he was hospitalized on Oct. 4, Dillon had been housed at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility at Lucasville, where he was a trash-crew worker.”

Mauser Rifle

Mauser Rifle

Former prosecutor Mike Miller said, “He killed purely for the pleasure of killing. He wanted the thrill. He was an evil man. I can’t say I have any sadness about him departing this earth.” Deanna Welling, sister-in-law of victim Don Welling, commented, “My knees shook a little when they told me, but at least he’s gone – we don’t have to worry about ever hearing from him or about him again. We’re relieved that he’s gone.” She also expressed gratitude toward Dillon’s friend Richard Fry for alerting authorities to the possibility that Dillon was the sniper, saying, “I’m glad that Richard Fry turned Dillon in. If not for him, it could have cost more lives.”

Jean Paxton, mother of victim Jamie Paxton, said that when notified of Dillon’s death, “It brought back a lot of emotions and memories that were always deep inside.” Lee Morrison writes that Jean Paxton noted, “Dillon was in prison nearly as long as her son was alive.” Morrison continues, “Dillon wrote to her twice, offering $1,000 to erect a monument where Jamie was killed or to establish a scholarship in Jamie’s name.”

Jean Paxton said, “I told him I didn’t need a monument up there to remind me what happened – all he wanted was to glorify himself and I told him I would never want anyone to receive a scholarship from a murderer. At that point, I wrote him that we have nothing to talk about. I never heard from him anymore.”

![]()