Established after the Bolsheviks took power in 1919, the gulags were forced labor camps where at least 1 million people died over the next 50 years.

During the days of Joseph Stalin, one wrong word could end with the secret police at your door, ready to drag you off to a Soviet gulag – one of the many forced labor camps where inmates worked until they died.

Historians estimate that nearly 14 million people were thrown into a gulag prison during Stalin’s reign.

Some were political prisoners, rounded up for speaking out against the Soviet regime. Others were criminals and thieves. And some were just ordinary people, caught cracking an unkind word about a Soviet official.

Still more inmates came from the Eastern Bloc of Europe – conquered countries that were made subservient to the Soviet regime.

The families of priests, professors, and important figures would be rounded up and sent off to the work camps, keeping them out of the way while the U.S.S.R. systematically erased their culture.

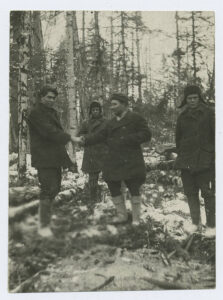

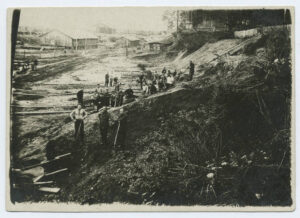

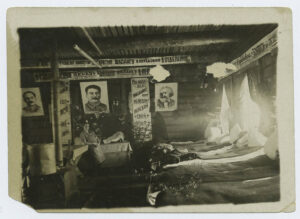

Wherever the gulag inmates came from, their fate was the same: backbreaking labor in freezing, remote locations with little protection from the elements and less food. These photographs tell their story:

The History Of The Gulags

The history of forced labor camps in Russia is a long one. Early examples of a labor-based penal system date back to the Russian empire, when the tsar instituted the first “katorga” camps in the 17th century.

Katorga was the term for a judicial ruling that exiled the convicted to Siberia or the Russian Far East, where there were few people and fewer towns.

There, prisoners would be forced to labor on the region’s deeply underdeveloped infrastructure — a job no one would voluntarily undertake.

But it was the government of Vladimir Lenin that transformed the Soviet gulag system and implemented it on a massive scale.

In the aftermath of the 1917 October revolution, Communist leaders found that there were a number of dangerous ideologies and people floating around Russia — and nobody knew how fatal an inspiring new ideology could be better than the leaders of the Russian Revolution.

They decided that it would be best if those who disagreed with the new order found somewhere else to be — and if the state could profit from free labor at the same time, all the better.

Publicly, they would refer to the updated katorga system as a “re-education” campaign; through hard labor, society’s uncooperative elements would learn to respect the common people and love the new dictatorship of the proletariat.

While Lenin ruled, there were some questions about both the morality and the efficacy of using forced labor to bring exiled workers into the Communist fold. These doubts didn’t stop the proliferation of new labor camps — but they did make progress relatively slow.

That all changed when Joseph Stalin took over after Vladimir Lenin’s death in 1924. Under Stalin’s rule, the Soviet gulag prisons became a nightmare of historic proportions.

Stalin Transforms The Soviet Gulag

The word “gulag” was born as an acronym. It stood for Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei, or, in English, Main Camp Administration.

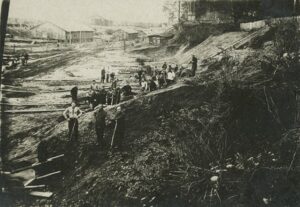

Two factors drove Stalin to expand the gulag prisons at a merciless pace. The first was the Soviet Union’s desperate need to industrialize.

Though the economic motives behind the new prison labor camps have been debated — some historians feel economic growth was simply a convenient perk of the plan, while others think it helped to drive arrests — few deny that prison labor played a substantial role in the Soviet Union’s new ability to harvest natural resources and take on massive construction projects.

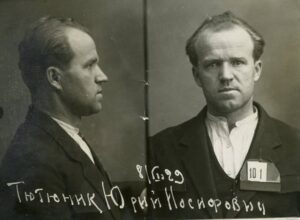

The other force at work was Stalin’s Great Purge, sometimes called the Great Terror. It was a crackdown on all forms of dissent — real and imagined — across the U.S.S.R.

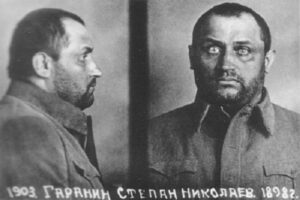

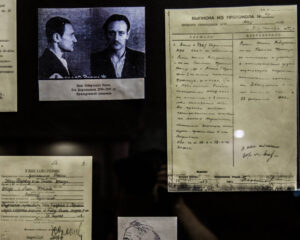

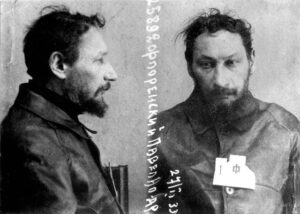

As Stalin sought to consolidate his power, suspicion fell on party members, “rich” peasants called kulaks, academics, and anyone said to have murmured a word against the country’s current direction. In the purge’s worst days, it was enough to simply be related to a dissenter — no man, woman, or child was above suspicion.

In two years, some 750,000 people were executed on the spot. One million more escaped execution — but were sent to the gulags.

Daily Life In The U.S.S.R.’s Forced Labor Camps

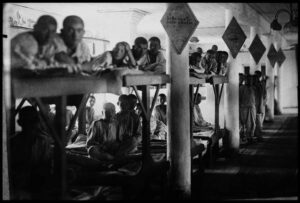

In the forced labor camps, conditions were brutal. Prisoners were barely fed. Stories even came out saying that the inmates had been caught hunting rats and wild dogs, snagging any living thing they could find for something to eat.

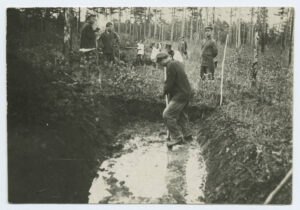

While starving, they were worked literally to the bone, using usually outdated supplies to do intense manual labor. The Russian gulag system, instead of relying on expensive technology, threw the sheer force of millions of men with crude hammers at a problem. Inmates worked until they collapsed, often literally dropping dead.

These laborers worked on massive projects, including the Moscow–Volga Canal, the White Sea–Baltic Canal, and the Kolyma Highway. Today, that highway is known as the “Road of Bones” because so many workers died building it that they used their bones in the foundation of the road.

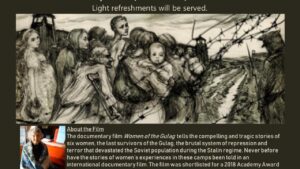

No exceptions were made for women, many of whom were only imprisoned because of the imagined crimes of their husbands or fathers. Their accounts are some of the most harrowing to emerge from the gulag prisons.

Women In The Gulag System

Though women were housed in barracks apart from the men, camp life did little to really separate the genders. Female prisoners were often the victims of rape and violence at the hands of both inmates and guards. Many reported the most effective survival strategy was to take a “prison husband” — a man who would exchange protection or rations for sexual favors.

If a woman had children, she would have to divide her own rations to feed them — sometimes as little as 140 grams of bread per day.

But for some of the female prisoners, simply being allowed to keep their own children was a blessing; many of the children in gulags were shipped to distant orphanages. Their papers were often lost or destroyed, making a reunion someday almost impossible.

After Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, the zeal that had sent thousands to the gulag prisons every year faded. Nikita Khrushchev, the next to take power, denounced many of Stalin’s policies, and separate orders freed those imprisoned for petty crimes and political dissidents.

By the time the last Soviet gulag closed its gates, millions had died. Some worked themselves to death, some had starved, and others were simply dragged out into the woods and shot. It is unlikely the world will ever have an accurate count of the lives lost in the camps.

Though Stalin’s successors ruled with a gentler hand, the damage had been done. Intellectual and cultural leaders had been wiped out, and the people had learned to live in fear.

![]()