What is now Kenya had the honor of being under the control of the British Empire beginning with the arrival of the Imperial East Africa Company in 1888. The British built a railroad through the country, which became known as British East Africa, using imported labor from India, and built large agricultural estates taking advantage of the fertility of the soil and the tropical climate. In 1920 the country was designated as a British colony and named Kenya for its tallest mountain peak. British farmers grew wealthy over the production of coffee and tea, using the native Kiyuku people as itinerant laborers.

As early as the 1890s there was resistance to the British opening of the lands and oppression of the natives. British troops stationed in the colony suppressed these uprisings harshly. In 1908 Winston Churchill expressed concern about the violence in East Africa, but not over the nature of the resistance or the harsh methods used by the British to control the natives. Instead, he was concerned over the reputation of the British should word of atrocities being committed to reach the House of Commons. Churchill did refer to the many victims as “helpless people”.

Through the 1920s and 1930s the British Colonial government classified the native workers as being in one of three categories; squatters, contractors, or casual. The British enacted ordinances which eliminated the rights of squatters, effectively forcing them to work for British settlers rather than for themselves, and kept labor costs low. Most of the laborers were of the Kikuyu people, and among them, there was rising discontent with the British settlers, who paid them poorly, offered little in the way of medical care, and housed them in primitive conditions.

A picture taken on September 7, 2015 shows a memorial in honour of victims of torture during the colonial era in Nairobi ahead of an unveiling ceremony on September 12. A British-funded memorial to victims of Kenya’s bloody Mau Mau rebellion will open in Nairobi in a rare example of former rulers commemorating a colonial uprising. AFP PHOTO / TONY KARUMBA (Photo credit should read TONY KARUMBA/AFP via Getty Images)

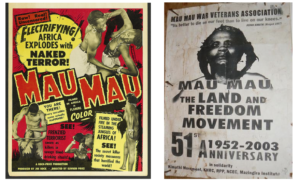

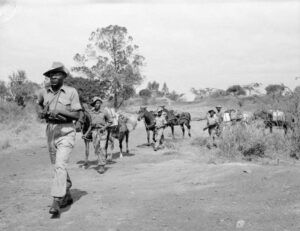

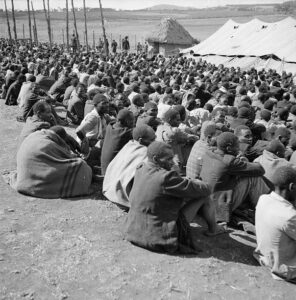

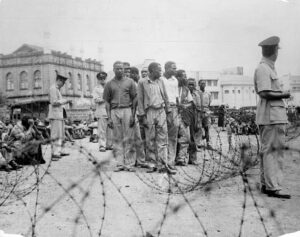

The Mau Mau were both a political organization and a paramilitary group which rose in revolt during the 1940s, eventually breaking into open warfare with the British and other Imperial troops in 1952. The majority of the Mau Mau revolutionaries were Kikuyu. After declaring an emergency the British pursued a policy of divide and conquer. Civil liberties were suspended. Kikuyu were rounded up into “work camps.” One and a half million people were held in camps or villages surrounded and fortified by British troops. The camps bore signs which read, “Labor and Freedom.” Torture and mass executions were common, including men being anally raped with bottles and other devices by guards.

Some Kiyuku were dragged by military vehicles until their bodies broke into pieces. Others were mauled by guard dogs before being executed. How many died in the British camps is unknown because the Colonial Office and Foreign Office connived to destroy the documentation. Officially released British records indicated that there were only 80,000 Kikuyu and other tribesmen incarcerated in the camps during the Mau Mau uprising, but recently discovered documents and other records indicate that nearly the entire civilian population was placed in the camps.

Lari Massacre

Mau Mau militants were guilty of numerous atrocities. The most notorious was their attack on the settlement of Lari, on the night of 25–26 March 1953, in which they herded Kikuyu men, women and children into huts and set fire to them, hacking down with pangas anyone who attempted escape, before throwing them back in to the burning huts. The attack at Lari was so extreme that “African policemen who saw the bodies of the victims . . . were physically sick and said ‘These people are animals. If I see one now I shall shoot with the greatest eagerness'”, and it “even shocked many Mau Mau supporters, some of whom would subsequently try to excuse the attack as ‘a mistake'”.

A retaliatory massacre was immediately perpetrated by African security forces who were partially overseen by British commanders. Official estimates place the death toll from the first Lari massacre at 74, and the second at 150, though neither of these figures account for those who ‘disappeared’. Whatever the actual number of victims, “he grim truth was that, for every person who died in Lari’s first massacre, at least two more were killed in retaliation in the second.”

Aside from the Lari massacres, Kikuyu were also tortured, mutilated and murdered by Mau Mau on many other occasions. Mau Mau racked up 1,819 murders of their fellow Africans, though again this number excludes the many additional hundreds who ‘disappeared’, whose bodies were never found. For their part, as already discussed, the British colonial government eventually instituted a system of detention and torture that was sanctioned at the highest levels of government in London, as well as carrying out or overseeing any number of extra-judicial executions and various massacres. One such killing spree was the Chuka massacre of June 1953, in which twenty African civilians, including a child, were shot in cold blood by soldiers of the 5th KAR B Company.

Thirty-two European and twenty-six Asian civilians were also murdered by Mau Mau militants, with similar numbers wounded. The most well known European victim was Michael Ruck, aged six, who was hacked to death with pangas along with his parents, Roger and Esme, and one of the Rucks’ farm workers, Muthura Nagahu, who had tried to help the family. Newspapers in Kenya and abroad published graphic murder details, including images of young Michael with bloodied teddy bears and trains strewn on his bedroom floor.

lectric shock was widely used, as well as cigarettes and fire. Bottles (often broken), gun barrels, knives, snakes, vermin, and hot eggs were thrust up men’s rectums and women’s vaginas. The screening teams whipped, shot, burned and mutilated Mau Mau suspects, ostensibly to gather intelligence for military operations and as court evidence.

A British officer describes his actions after capturing three Mau Mau suspects:WARNING

I stuck my revolver right in his grinning mouth and I said something, I don’t remember what, and I pulled the trigger. His brains went all over the side of the police station. The other two Mickeys were standing there looking blank. I said to them that if they didn’t tell me where to find the rest of the gang I’d kill them too. They didn’t say a word so I shot them both. One wasn’t dead so I shot him in the ear. When the sub-inspector drove up, I told him that the Mickeys tried to escape. He didn’t believe me but all he said was “bury them and see the wall is cleared up.”

Settler groups, displeased with the government’s response to the increasing Mau Mau threat created their own units to combat the Mau Mau. One settler with the Kenya Police Reserve’s Special Branch described an interrogation of a Mau Mau suspect: “By the time I cut his balls off he had no ears, and his eyeball, the right one, I think, was hanging out of its socket. Too bad, he died before we got much out of him.”

In 1952 the poisonous latex of the African milk bush was used by members of Mau Mau to kill cattle in an incident of biological warfare.

![]()