For years, the unstoppable Huns sacked city after city until a Germanic-Roman alliance stopped them.

“Whether revered as fearless warriors or reviled as murderous savages, the original Huns came riding out of the Eurasian Steppe during the Late Antiquity like a whirlwind.”

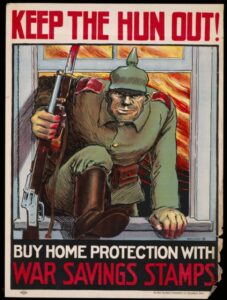

IT WAS JULY 27, 1900. A German expeditionary force was preparing to set sail for China from the North Sea port of Bremerhaven.

Anti-imperialist rebels in the Far East, known as Yihetuans or Boxers, had launched an insurgency that was threatening European and American trade interests there. Now a coalition of powers known as the Eight-Nation Alliance was dispatching troops to put down the uprising.

As the German soldiers assembled to embark, their ruler, Kaiser Wilhelm II, addressed the brigade. During the speech, the Hohenzollern emperor urged his men to be ruthless in the coming fight, to give no quarter and to take no prisoners.

In the face of an unstoppable and destructive Hunnic invasion, Ermanaric’s final act was a (probable) ritualistic death ceremony in which he ended his own life

“Just as a thousand years ago, the Huns under their king, Attila, made a name for themselves, one that even today makes them seem mighty in history and legend, may the name ‘German’ be affirmed by you in such a way.”

They were words that would famously come back to haunt Wilhelm. Fourteen years later, as his soldiers laid waste to Belgium in the opening weeks of the First World War, Allied propagandists would label all Germans as Huns. The name would stick and even be revived in 1939.

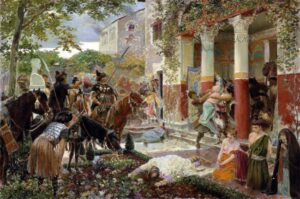

Whether revered as fearless warriors or reviled as murderous savages, history’s original Huns came riding out of the Eurasian Steppe during the Late Antiquity like a whirlwind. To be sure, the Roman world had seen “barbarians” before, but nothing like this. Over the years that followed, the mysterious invaders pillaged and slaughtered their way across both the Western and Eastern empires, razing towns, demanding vast tributes in gold and driving legions of refugees before them. Yet by the end of the 5th Century, they vanished from Europe seemingly without a trace.

Although gone, the Huns would not be forgotten. Their name would live on into modern times as a byword for brutality. But what do we actually know about the Huns? Where did they come from? What were they like? Here are 10 amazing facts about the ancient world’s most feared raiders.

Their origin is a mystery

No one is sure exactly where the Huns came from, but some historians have theorized that the nomadic warriors that shook up the Roman world were castoffs of the Xiongnu peoples of ancient Mongolia. After generations of raiding China, the Xiongnu were defeated sometime in the late 1st Century and scattered. Some supposedly began migrating westward, honing their fighting skills and picking up factions of wanderers along the way. The name Hun itself might actually be based on an old Turkic word for ‘ferocious.’ Others suggest the moniker comes from the Persian hūnarā, meaning ‘skilled.’ Both seem to reference to the Huns’ combat prowess. A final theory posits that the word is derived from the name of the Ongi River in Mongolia, possibly the band’s original homeland. Regardless of the etymology, it would take the Huns generations to cross Asia and reach the edge of Europe. When they arrived, all hell would break loose.

Their sudden appearance rocked Europe

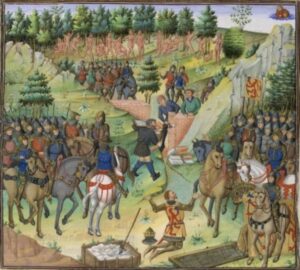

The Huns burst onto the scene in Europe in 376 CE. According to historian Ammianus Marcellinus, that’s when the first of them crossed the Volga River and stormed territory controlled by Sythians. As they pushed west, the Huns forded the River Don and ravaged the settlements they found there. Their sudden arrival on the fringes of the Roman world touched off a refugee crisis known as the Migration Period in which displaced Goths streamed into Roman-controlled territory seeking refuge from the strange invaders. Emperor Valens granted the dispossessed shelter, but the empire was ultimately unable to provide for the homeless hoardes descending into his territory. Soon the refugees rose in rebellion against their Roman protectors.

They were masters of hit-and-run warfare

Unlike Roman armies, which had long relied on decisive pitched battles using massed infantry formations, the Huns were mounted fighters who preferred swift attacks, feints and retreats. They travelled in fast-moving columns with replacement horses in tow, which often created the impression that they were a much larger army. Although armed with swords and short lances, it was their powerful recurve bows for which they were the most famous. The four-foot weapons were handy enough for trained riders to launch salvos of arrows while at a full gallop. Hun missiles were tipped with iron trilobates, which could punch through armour more easily than conventional flat arrowheads. Huns preferred to engage enemy armies from long ranges, riding in close, encircling their foes and showering opponents with projectiles before then withdrawing to safety. Hun warriors typically wore light leather armour or sometimes chain mail.

The Romans thought the Huns signaled the end of the world

The sudden appearance of the Huns coincided with a growing belief among Rome’s 4th Century Christians that the end of the world was at hand. Many speculated that the invaders were in fact the mythical armies of Gog and Magog, two supposedly unholy nations referenced in the Old Testament whose final defeat by the Messiah’s would usher in the Apocalypse. According to later legends, Alexander the Great himself had encountered strange peoples on his travels through Asia and ordered his troops to erected a massive wall to contain them. The story holds that the young Macedonian king carved a prophecy onto the edifice warning that if the barrier was ever breached and those behind it freed, it would spell the end of the world.

The Huns certainly seemed demonic

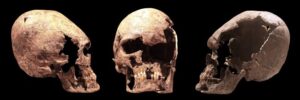

To Europeans, the Huns certainly must have looked as if they’d ridden straight out of the infernal regions. They practiced head-binding, a form of artificial cranial deformation that produced unnatural elongated skulls. Europeans were also clearly unfamiliar with the Huns’ mostly Asiatic appearance. Eyewitnesses described them as a “scarcely human” and characterized their language having “but slight resemblance to human speech.” According to one contemporary chronicler, the Huns “…made their foes flee in horror because their swarthy aspect was fearful, and they had, if I may call it so, a sort of shapeless lump, not a head, with pin-holes rather than eyes. They live in the form of men, they have the cruelty of wild beasts.”

Many Europeans flocked to the Hun armies

Although Roman chroniclers painted a decidedly unflattering caricature of the Huns, evidence suggests that the raiders themselves weren’t too choosey about who could join their ranks. Hun armies attracted conscripts from their various conquered territories and castoffs from the Alans and various Gothic peoples flocked to their banner. Grave sites found in Central Europe dating from the 5th Century contained the remains of European peoples buried with Hunnic accoutrements and even elongated skulls. This suggesting many were either assimilated by the Huns or at least aspired to be like them.

The Huns got rich off protection money

By 395 CE, Hun war bands drove into the Balkans onto land controlled by what was now the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. Unable to defeat the attackers, the rulers in Constantinople sought to appease them with gold. In fact, the emperor’s envoys negotiated a yearly tribute of treasure in exchange for peace. The calm would be short-lived; the Huns returned to the warpath when the Romans ran low on money.

Attila was their last king

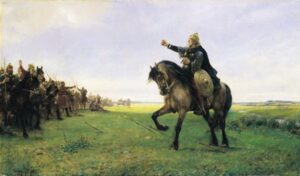

Over decades of intermittent fighting, the Huns had splintered into various factions that were scattered across Eastern and Central Europe. In 434, two brothers from the Hun aristocracy, Attila and Bleda, rose to power and set out to unify the disparate tribes. As their confederation solidified, the pair renewed their wars with the Eastern Empire before pivoting east to mount an ambitious campaign against the Persians, known then as the Sasanians. Defeated in what is now Armenia, the Huns returned to Europe with a vengeance threatening both the Eastern and Western empires. Bleda died in 445, possibly murdered by his own brother, leaving Attila the sole ruler. In 450, the Hun king claimed the sister of the Western Roman emperor Valentinian III as his bride and demanded vast swaths of land as her dowry. When his ultimatum was refused Attila invaded Italy and in 451 galloped into Roman Gaul, modern-day France, at the head of a vast army. There he was intercepted by a force led by the Roman general Flavius Aetius and the Visigoth king Theodoric I. Who won the epic Battle of the Catalaunian Plains remains unclear, but what is certain is that sometime after the clash, Attila withdrew from Gaul altogether and refocused his wrath on Italy once more.

The Huns disappeared very quickly

Despite his reputation as a fierce warrior, it wasn’t an enemy’s sword that finally felled Attila — it was a bad nosebleed. The nasal hemorrhage occurred on the night of his wedding in 453 to a young Germanic princess named Ildico. He supposedly choked to death on the blood. When his lieutenants found him the next day, they were reportedly so stricken with grief they pulled all their hair out and cut deep gashes in their faces. “The renowned warrior might be mourned, not by effeminate wailings and tears, but by the blood of men,” one chronicler recorded. Following his death, Attila’s three sons fought bitterly for power while the various Germanic tribes once beholden to the late conqueror rebelled. The Battle of Nedao, which probably took place in 454 in what is now Hungary, saw the Huns decisively beaten and scattered by their former vassals. Surviving Hun raiders continued to appear occasionally in Byzantine territory until 469, after which they seemed to have vanished for good, likely returning to Asia and obscurity.

Their legend lived on long after they were gone

Despite their rapid decline and fall, the Huns left a lasting mark on Europe. Modern-day Hungarians have long claimed to be their descendants. Although the country does exist on territory once controlled by Attila and his followers, there is little evidence to suggest that the earliest Hungarians, known as Magyars, were actually kin of the original Hun. Throughout the Middle Ages, Attila and his followers featured prominently in Europe’s Christian folklore. The city of Rome was supposedly saved from a Hun onslaught after Pope Leo I confronted the marauders with the help of the sword-wielding spirits of the apostles Peter and Paul. In another tale, Saint Ursula was martyred by an army of Huns besieging Cologne after she and 11,000 virgins refused to surrender their bodies to the invaders. But nowhere did the Huns figure more prominently than in Medieval Germanic literature. The influential poem The Battle of the Goths and Huns chronicles the wars of the 4th and 5th centuries, as do a series of Norse sagas and German legends. It’s no surprise that all those years later, Kaiser Wilhelm II invoked the Huns as fearsome warriors when addressing his troops in 1900.

![]()