Police have been using the snapshots in criminal investigations since the advent of commercial photography

In the spring of 1841, just after finishing his inauguration speech, William Henry Harrison became the first United States president to be photographed. The portrait was a daguerreotype, created with a newly invented process that produced a photograph in minutes rather than hours.

While Harrison’s image was lost to history, a photographer snapped the oldest surviving presidential photograph just two years later: a portrait of John Quincy Adams, taken over a decade after his time in office. Sitting in front of a fireplace and a stack of books, with a sharp gaze fixed just below the camera lens, the politician is portrayed with a stately solemnity.

Since then, many famous photos of presidents have become etched in the American psyche: Harry Truman holding the prematurely printed newspaper declaring his defeat in the 1948 election, Richard Nixon boarding his helicopter after resigning in 1974, George W. Bush learning of the 9/11 attacks in 2001, Barack Obama sitting in the Situation Room during the mission to kill Osama bin Laden in 2011.

During his term, Donald Trump also appeared in a number of memorable images. Soon, he may be the subject of a new photographic first: the presidential mug shot.

Last week, Trump was indicted by a Manhattan grand jury on charges likely involving a $130,000 payout made to an adult-film actress during the 2016 presidential election. He’s expected to turn himself in tomorrow, becoming the first former president to face criminal charges. (The first—and so far only—sitting president to be arrested was Ulysses S. Grant, who was pulled over for speeding in his horse-drawn carriage in 1872.)

Once Trump surrenders at the Manhattan district attorney’s office, he will likely be fingerprinted. But whether he’ll get a mug shot taken—and whether this image would then be released to the public—remains unclear

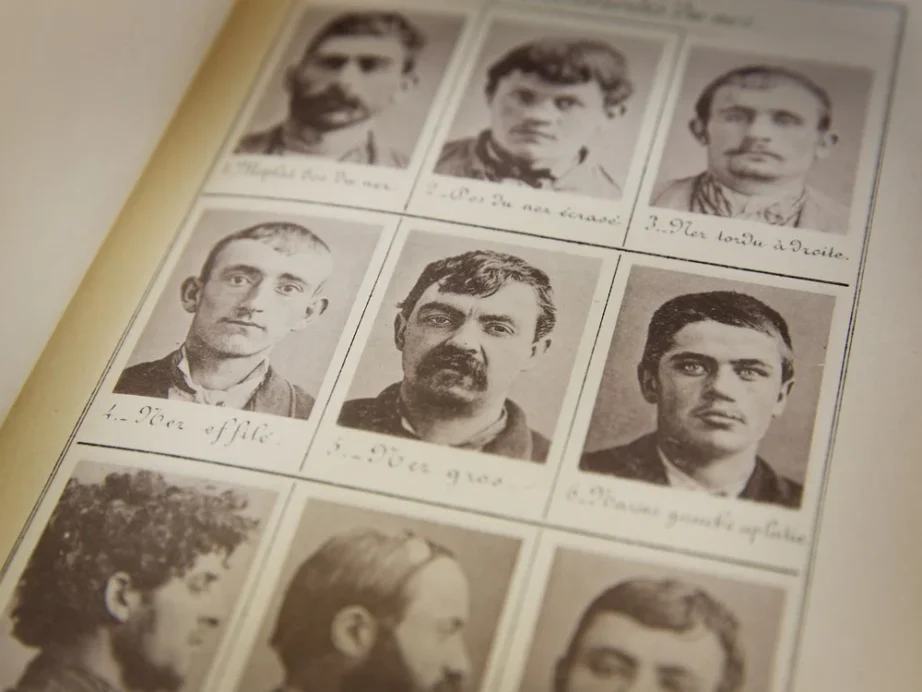

A rogues’ gallery in New York City in 1909 George Grantham Bain collection / Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

Like the presidential portrait, the mug shot’s history begins as early as the 1840s, when prisoners in Belgium were photographed so they could be identified if they committed crimes after their sentences ended. Over the following decades, police departments around the world began experimenting with ways to incorporate photography into their work. In the U.S., police created rogues’ galleries of mug shots, sometimes even publishing them and encouraging upstanding citizens to keep a watchful eye out for troublemakers.

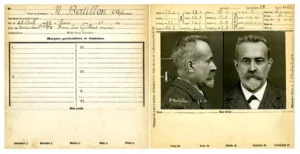

The practice, however, didn’t become standardized until the 1880s, when Alphonse Bertillon, chief of criminal identification for the Paris police, streamlined the process.

Bertillon’s mug shot consisted of two photographs—one facing the camera, the other in profile—attached to a written description of physical features and certain measurements, such as the size of someone’s ear or foot. Together, these elements were called a portrait parlé, or “speaking image.”

“Bertillon designed the portrait parlé in an effort to catch masters of disguise who committed crimes under different aliases,” wrote Shawn Michelle Smith in the journal Aperture in 2018. “He proposed that although a repeat offender might conceal his identity, one would be able to discover him if his physical measurements matched those of ‘another’ offender already recorded.”

In 1908, the New York City Police Department compiled a series of images showing how to properly take a mug shot and the accompanying measurements. According to Smith, some of these images even “simulate people who refuse to sit for their mug shots and are wrestled into submission before the camera by multiple men, suggesting that not all subjects would be amenable to these extensive measurements.”

Soon after, “Bertillon’s method of recording anthropometric data lost out to the more reliable process of fingerprinting,” wrote Slate’s Julia Felsenthal in 2010.

The mug shot, however, endured.

“Whenever you go through an airport or … a train station … and somebody asks to see your identification document, that all has roots in the late 1800s and the work of people like Bertillon and his contemporaries,” Jonathan Finn, a police photography expert, told NPR’s Hansi Lo Wang in 2016.

Today, the vast majority of mug shots portray people who aren’t famous—and sometimes even people who haven’t committed crimes. Mug shots can be published in newspapers before the subject is actually convicted. In recent years, public opinion has started turning against the practice, and some newsrooms have stopped using mug shots altogether.

“Mug shot slideshows whose primary purpose is to generate page views will no longer appear on our websites,” Mark Lorando, a managing editor at the Houston Chronicle, told the Marshall Project’s Keri Blakinger in 2020. “We’re better than that.”

Among celebrities, mug shots are staples of tabloid gossip. They are “a genre unto themselves, notable for providing that rare opportunity to see the rich and beautiful brought low,” writes the Washington Post’s Gillian Brockell.

In specific contexts, such as the civil rights movement, famous mug shots are seen as a mark of integrity. Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr. and many other famous activists had mug shots taken when they were arrested for protesting.

Exceptions also exist for celebrities who have crafted an image involving an outlaw spirit as a central tenet. Throughout his career, Johnny Cash spent several one-night stints behind bars, and he spun one of those experiences into the song “Starkville City Jail.” Today, a T-shirt with Cash’s mugshot and the text “American Rebel” is on sale in the singer’s official store for $25.

![]()