A short history of a blood soaked toothy snarl

Today it’s hard to imagine a vampire without fangs. The undead have appeared in western folklore since at least the 18th century, yet most historians agree it was not until Bram Stoker’s classic 1897 novel Dracula that fangs became widely associated with vampires in the popular imagination—and even in Bela Lugosi’s landmark 1931 portrayal, Dracula didn’t have fangs.

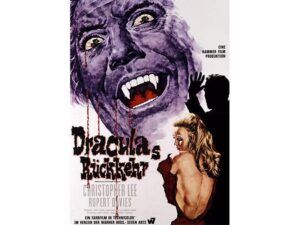

While fangs began to appear on the big screen in the 1950s in Turkish and Mexican productions of Dracula, true vampire buffs say it was the 1958 British Hammer Films version, starring a sexy Christopher Lee in the title role, that popularized fangs in movies. (Theater previously had no use for them: In an era before stage microphones, actors needed to be able to articulate clearly and project to the audience, and fake fangs distort speech.)

Fake fangs made their way to the public thanks to Halloween. Brian Cronin, a longtime entertainment journalist, notes that the 1964 vampire mask marketed by Ben Cooper Inc., then one of the largest U.S. manufacturers of Halloween costumes, did not have fangs; by 1978 it did. In the intervening 14 years, Lee appeared in 12 vampire films—and thereafter Halloween was a veritable festival of fake chompers.

In the 1990s, role-playing tabletop games like Vampire: The Masquerade even inspired folks to join a community of people who identified as “real vampires,” according to J. Gordon Melton, distinguished professor at Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion, who has written and edited scholarly books about vampires. Many “real vampires” dress the part year-round, complete with fangs.

Still, this lively subculture accounts for just a fraction of the fangs sold globally each year: Launched in 1993, Scarecrow Vampire Fangs now supplies around 250,000 sets of fangs to over 35 countries annually, mostly for Halloween.

Co-founder Linda Camplese credits the popularity of her goods to increased adult participation in Halloween—and to the undying popularity of vampires: “People like the idea of living forever and being powerful,” Camplese says.

![]()